Once upon a time, when I was only fifteen years old, I boarded a weather-beaten old passenger liner and sailed out from the New York harbor. I was on my way, by a very roundabout route, to a little city in the Austrian mountains. The ship was registered, I suppose, in some place around Argentina. The food was terrible but who cared? I was with a group of Boy Scouts, most of whom had never set foot outside their own states. The voyage was planned to last ten days or so, with a visit to some place called the Azores, followed by an expedition into the Casbah which was located in the port city of Algiers. After that eye-opening experience we were then to finish by cruising across the Mediterranean Sea and into the Bay of Naples. Finally, after the whole thing was over, we were to end up in Paris. Pretty unnerving for a guy from Louisiana. Oddly enough, as I think back about it now, I had no books with me. I had not yet discovered what I later found to be indispensable, in fact one of the most important things for me, the mystery of words.

It was, nevertheless, a journey filled with new thoughts. Keeping watch over the crew scrubbing the decks around midnight introduced me to, in case I should ever need it, an entirely new approach to mopping. And, of course, the open horizon, without another ship in sight, made me wonder if Marco Polo had known what he was doing when he took a different route.

The most interesting moment came when I ambled into a large sitting room on the main deck. Everyone there, seated in overstuffed chairs, was dressed like he was going to pay a visit to an archduke somewhere in the Pyrenees. I had on short pants. And then, as tea and dainty cookies were being served, these four men who looked like they might have escaped from Count Dracula’s underground laboratory came out. I sized up the details. Black suits, black ties, scarce hair on balding heads, instrument cases. This was not an encouraging sight.

I had taken a cup of tea and as many cookies as I could hold in one hand. Then I watched as they unpacked and started playing their instruments. I realized, pretty quickly, that I was really not all that accustomed to string quartets. My mother, who had understood the southern requirements for cultural education, had, contrary to certain misgivings, occasionally taken me to a concert. However, those expeditions were nothing like this. I started checking out the way to the door. Even though I hadn’t fallen overboard yet, I still had a creepie feeling that I was about to lose my grip on something. The Boy Scout motto was the somewhat overly optimistic slogan, “Be Prepared.” (For precisely what, I always wondered. I really wanted to know). I definitely was not prepared for the music that I later came to surmise was written by someone like Haydn. To my own surprise, I overcame my wariness and, not only stayed that afternoon but returned day after day at four o’clock. I accepted the incongruity of it all even though I felt that I was an ambassador from the twentieth century. It was a little mystifying. Outdated Latino-Euro ambience. Drapes that had probably been hung in the good witch’s castle for about one hundred years. Carpets that Napoleon had replaced when he landed on the island of Elba. Paintings by someone who had flunked out of Michelangelo’s weekly art classes. Serving dishes that had definitely not come from Macy’s.

There was, to my surprise, something more intriguing about it than any of that. I had been unaccountably touched by the whole experience. And yet, I did not really know how to think about it. Having too few books in my own history to provide perspective, I could not bring it together. It was as though I had been admitted into a world where I was being gradually summoned to swim in greater depths. I was certainly aware that I had never swum in this pool. Later, when books began to give me tickets to other destinations, I had begun to lose many of those hesitations.In time I might have been tempted to reformulate a line from the book of James to the effect that faith, without the flight of soaring books to lift your life is, if not dead, at least permanently grounded. I would not have guessed it at this stage, but I would learn in time that such literary flights would not always be an easy trip. Books sometimes displaced the horizon in your world without warnings and left you with questions that you had never asked. They could take you into places from which you were not sure that you could return. And when and where, I have now forgotten, books on theology eventually came my way they usually introduced a haunting dimension. They answered few of my questions, often seemed to be remarkably assured, and frequently seemed to have been written for someone else. They only deepened the spiritual mystery.

Years slipped by. I was able to enroll in a college that took me far away. And yet, while the campus had most of the resources one might want, I was not completely at peace. There was to be discovered, however, a way out. Just to the north of the campus were the woods. And as the years passed, I frequently left the campus for the forest, and it was there that I discovered something different. No unusual drawing room. No string quartet. No tea and cookies. But something more solitary and more sublime.

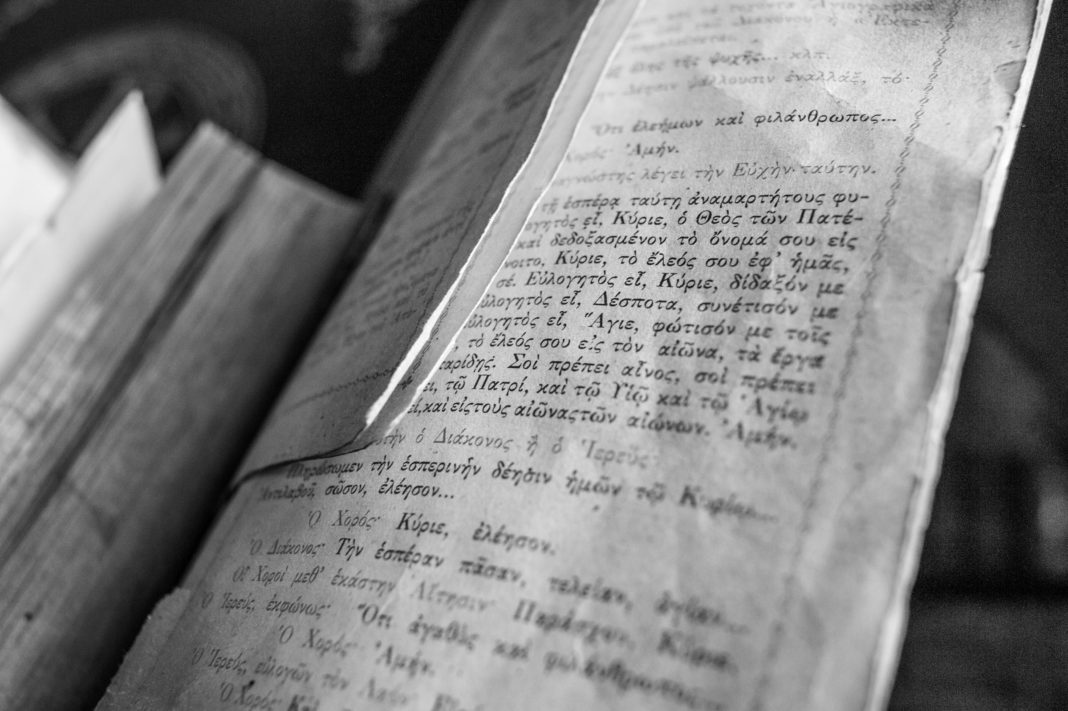

I had discovered books by then, and I usually took a significant work of some kind with me. And there, seated beside the river, I began to understand. It had to do with the play of sentences that, formed into books, admitted us into the minds of those who had lived before us. They had become invitations that were nearly irresistible. When I read Frans Kafka’s The Trial, Henry Adam’s Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres, or my aunt Lillian’s Southern Plantation I realized that I had begun to sail on seas that were filled with wondrous things. And in a sense, I became even more bewitched than when I had been listening to Haydn’s string quartets. It did not have to be a book that was on an edge, like those by Flannery O’Conner or James Joyce, from whose minds’ words flowed as from mountain springs. It was actually my experience that most authors that I read welcomed me into uncharted territories and left me, as it were, clinging to a cliffside path. I could not escape the thought that when we had been given the gift of words and sentences, God had entrusted us with a very great mystery. And a very exacting responsibility.It was not long before I began to explore the books whose authors had undertaken to write about God. They flowed through my life. Past seminary, past further graduate school, past other times and places until I met one whose sense of obligation to both the Scripture and the spiritual life had exceeded many others in his own time and even in many years that lay ahead. It was the third century scholar Origen of Alexandria who later settled in Caesarea. The most well-read expositor of Scripture in his day and the founder of a library and a school, his adventurous cosmic speculations stirred some and deeply unnerved others. Nevertheless, here is a remarkable thing to remember about him. His tidal wave of pious insight, recorded in Greek, rolled on until it washed up on the shores of Cappadocia and enfolded those who have been credited with the development of the well-known Nicaean doctrines.

These in time included those which were constructed into the universal creeds that were intended to call forth the unity of the Christian church. Gregory of Nazianzus, who studied under the rhetoricians and philosophers in Athens for ten years and his colleague known later as Basil the Great had also edited a number of Origen’s writings which they entitled the Philocalia. And this led to a broader spread of Origen’s thought. Their young student and prodigy, Evagrius Ponticus, left their sides, settled in the Egyptian desert, and became the most prolific writer and advisor in the early wilderness monastic tradition (The Praktikos and Chapters on Prayer, Trappist, Kentucky: Cistercian Publications, 1972; Ad Monachos, New York: The Newman Press, 2013). It was only a short period of time before his formulation of the moral life became integral with the thought of John Cassian who in turn provided guidance for the Christian ethical life as later interpreted by Gregory the Great. And on it went. From one mind on fire to another. Or as it was later put in more general words, from one generation to another. Regardless of how the miracle occurs, in the hands of those skilled with words, the power of Christ continues to burn until it reaches us. In the course of this process people still hear the voice whispering mysteriously to them that they are summoned to join this stumbling procession.

Approximately one hundred years later a theologian from a Latin tradition was born. His inspiration was to follow an alternative historic path, one that would be deeply argued and significantly structured in different ways. His brilliance unfolded gradually and developed into a more dialectic way of expressing his convictions. Even when the Roman emperor Justin had forbidden Christians to teach, he proceeded to develop a significantly distinctive pattern of thought. Its sheer cognitive authority easily swept into the searching minds of many of those who came after him. He had studied philosophy for many years previously before being touched and redirected by Scripture. In the course of that he had become a Christian. And in the ensuing years he became the first person to write a systematic metaphysical treatise on the Trinity in Latin.

Marius Victorinus had been born in Africa between 281 and 291, made his way to Rome, and was stirred into the intellectual caldron of the age. This complex mix combined the Roman classical tradition, the Hellenistic Neoplatonist writers, and the Christian communities. At an early point, Victorinus translated the Greek texts of Neoplatonists, likely those by Plotinus and Porphyry, into Latin, and thus he paved the way for them to fall, years later, into Augustine’s hands. Augustine read them and in his Confessions at 7.9.31 he recorded his indebtedness to them. Who would have thought that this mysterious flow of words would come together so indirectly in the formation of a Christian mind?

There is still more to consider. Victorinus had absorbed some interesting intellectual sources into his own mind, ones that we are not likely to check out from our local library. In 1978, Mary T. Clark of Manhattanville College wrote this in the introduction to her translation of Victorinus’ Theological Treatises on the Trinity, “To get the most out of Victorinus’ treatise on the Trinity one should be familiar with all of Neoplatonism as well as the commentaries on the Categories of Aristotle, the commentary tradition concerned with the Sophist, the Parmenides, the Timaeus of Plato, with the ‘Chaldean Oracles’ and especially with the anonymous commentary on the Parmenides, a common source for Victorinus” (“Introduction,” Theological Treatises on the Trinity,” Washington: The Catholic University of America Press, 1981, p.18). This, of course, is more than a little overwhelming for almost anyone. Nevertheless, perhaps we might gather our thoughts together with a point of view like this, “a well-fortified mind could be a joy for the Lord to use.”

What really remains for us to consider about him is the way in which the spiritual heat within his Christian faith, smoldering and melting, remolded the intellectual language of his culture. Through his own gifts, he extended the meanings of words and created neologisms (new terms) that had heretofore been unknown. Their use then continued throughout the long era of medieval studies in philosophy and theology.

So here we have the wonder of these two currents together, one from the Greek heritage and one from the Latin. While they seem to be magnificently distinctive, with different kinds of words, they meet each other. The cultural balance works. And perhaps we will find that even in other fields of expression and art, our voices give new perspectives to one another.

And thus, as we look more deeply into all of this, it tempts us to think that words become markers of the hidden movements in our souls. That which we learn molds us. That which we use discloses us. That which we increasingly hear in public discourse shames us. And that which is changed by the influence of political ideology worries us. More significant yet, can we become sufficiently perceptive to recognize the consequences that are at risk when we begin to shred the mystery that has been held in trust, like sacred diamonds in the crown of faith, in history’s traditional theological terms?

Victorinus’ unusual facility with philosophical concepts led to his remarkable capacity for defending this heritage of Christian theology and blowing away the misjudgments of the surrounding Arian critics. Mystery, one might say, when formed in us by Christ, gives to us the wondrous dance of spell binding words. And that is where the awesome responsibility begins.

Looking back, I wonder about the unexpected pauses in any of our journeys. Could an antic transhistorical step into another time, on an old passenger ship at sea, have created a sense of curiosity in an adolescent mind? And later, could those afternoons beside a river in a forest, thinking about the books that I was reading, have suggested to me that words could become the jewels that enable our minds to measure more than time? And could a discovery, in a very amateurish glance, into the realms of music have disclosed that Antonio Vivaldi, who in time became a priest, and J.S. Bach were born only seven years apart, one in Italy and one in Germany, and perhaps as a partial result of that their compositions provided lilting contrasts. They are endlessly different. Together, however, they give us complementing melodic structures out of different minds and cultures, both being composed to the glory of God.

What this suggests are a few exceedingly difficult questions for us. Why did God pour theology into the beauty of the swirling, complementing mystery of words? Did he intentionally leave us with these very fragile, malleable mediums to indicate his truth? We have no more than speculation about that now. What we do come to recognize is that the personal struggles in our lives are in a remarkable balance with the broken places in the words that bear spiritual truth. And words do break and come unglued even as we treasure them. Neglected sometimes for years, word’s meanings are often more frail than one might think. However, this might not be so bad. We can eventually even begin to trust a certain type of frailty, not because we are naive about its incompleteness but because we are beginning to be aware of something more than strength. Perhaps, in this respect, it is like the Cross.

When poised directly against brokenness we are sometimes surprised by trust. Theological insight does not ride on the rails of mathematical certainty. But does trust not come to us, in precarious moments, from the echoes of words that we barely understand? And that, actually, may be both the irony and the beauty of it. Who can understand a piece by Vivaldi or Bach, or even our old nemesis, Haydn, for that matter? They come to us as gifts. And who can truly understand a gift

Each gift remains a mystery until it is opened. This is especially so with words that have the ring of theology about them. Formed through something akin to frailty, molded through what some have called askesis, that is a disciplined life, and inspired by the well of scriptural wisdom, we hardly know how to go about opening them. There is, however, in this case, the nuance of a promise about them. It may be a very faint promise, for after all it has come a long way, like the light from a distant star, for after all this promise has been reverberating across the years until it has come to us.

Who wants to overlook a promise of this kind? It may seem strange to us at first, but a present could hold an exceptionally valuable promise. However, even opening a present like this can sometimes be delayed. And theological words, as presents, can sometimes seem to be the trickiest of all. They tease our minds until someone beyond our minds, the one who actually gives them, breaks them open. Even so, is there not a sense in which theological words are always destined to remain beyond our grasp? We may not know the meaning of such a melodious flow of his words until we are eventually summoned home. However, while we are still here, does he not send us, like Vivaldi and Bach, into vividly balanced dimensions of beauty, into words, touching, dividing and recombining as they go. It remains a voyage, like one around the Azores, of bewilderment and wonder.

To be assured, this many faceted mystery may even take us further. Will someone really come? Seated on a wooded riverbank, we may feel that we have only been trusted with a small gift, a gift of waiting at this point. But that is not so small a gift. One day, when we least expect it, someone may be preparing to sprinkle hand-fuls of words that glow like diamonds into our brains.

One never knows, it might also be true that, even if we have hardly ever touched a book, he still calls us to serve him in illuminating ways. After all, who knows the origins of thought, who has wrapped the gift of wonder in words, may also have more ways to speak of Christ. The intensity of something we are yet to grasp, the empty tomb, if we put it that way, does shatter all things, including the beauty of our words and the limitations of our minds. To enjoy our little time of waiting, before our journey leads us to that which is the awesome best, we might even want to sit a spell. To sum our courage and to listen to, well, perhaps I really ought not to suggest it, something like Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C Major. That could even remind us that the most mysterious words, the ones for which we all wait, will in time tell us even more than we could ever ask.