Martin Luther had a mistress. It can be denied and has been many times. But the fact is he did, or at least he thought he did, and he struggled with her for many years, especially as a young man. There is much about this relationship we do not know, but we do know this: rightly or wrongly, he sometimes called her “Reason.”

It is complicated, of course. But to understand this relationship we must be clear: The Protestant Reformers had nothing against reason as such. On the contrary, they loved reason and believed Christians should always strive to be reasonable. They taught that reason is a gift of God that should be cherished, cultivated, and exercised whenever possible, and should never be taken for granted, neglected, or denigrated.

Nevertheless, reason alone cannot tell us, as Calvin says, “who the true God is or what sort of God he wishes to be toward us” (Institutes 2.2.1). Nor can reason alone tell us who we truly are. Reason can be a useful tool but never a substitute for revelation. It can be a servant of revelation but never its master. Luther struggled to maintain the order of this relationship. Yet he sometimes got confused and it created real problems for him, especially when he contemplated himself.

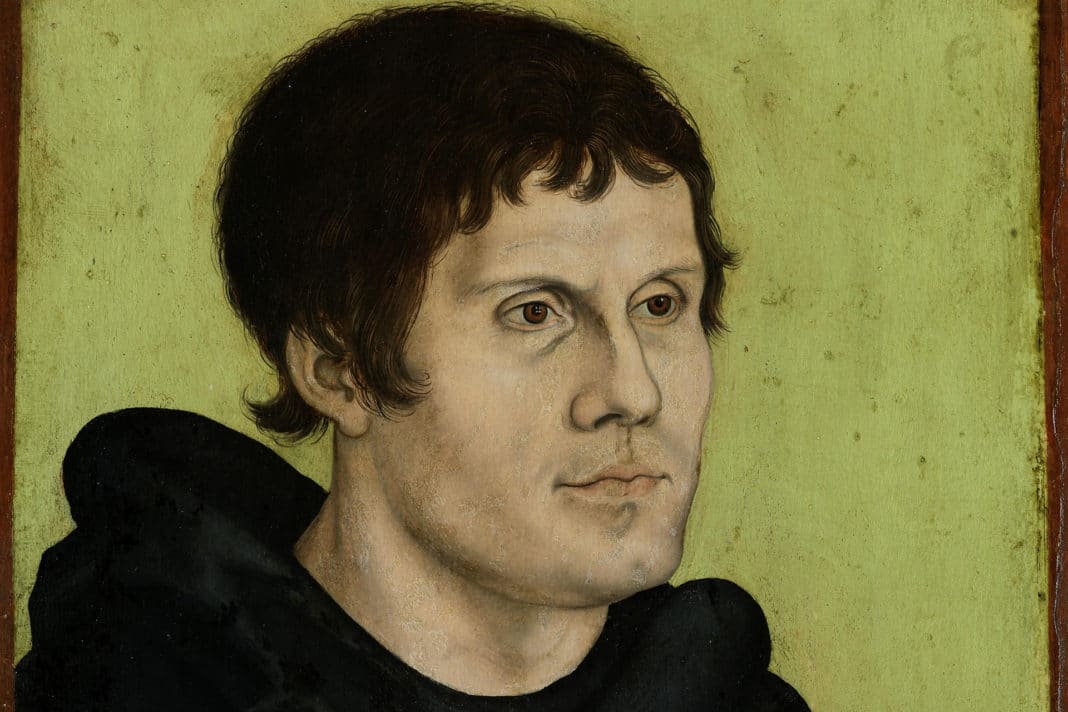

Luther was an exceedingly rational person who had been schooled according to the highest, most exacting standards of rationality. Thus, when it came to being justified by faith, even after he understood better what it meant, he was still often tempted to look for rational demonstration or proof of his righteousness within himself rather than receive it by faith as a pure gift.

As a young monk he often prayed and fasted for days, performed all manner of good works, engaged in all sorts of extreme acetic practices such as mortifications, flagellations of the flesh, vigils, pilgrimages, penance, etc. He later said: “If ever a monk got to heaven by his monkery it was I.” He would confess his sins for hours and receive absolution only to return moments later, recalling yet another peccadillo, driving his confessor, Father Staupitz, nearly crazy until finally, exasperated, he told Luther to go out for once and commit a real sin![1]

Luther later reflected: “My situation was that, although an impeccable monk, I stood before God as a sinner troubled in conscience, and I had no confidence that my merit would assuage him. Therefore I did not love a just and angry God, but rather hated and murmured against him.”[2] Luther admitted it was he who was angry, and not only because he could not please God, but because he could not please himself. He wanted a righteousness of his own (contra Phil. 3:9), not a “borrowed righteous-ness” from Christ. When he discovered that the former was the sort the devil promoted and the latter was the only righteousness worth having, it changed everything.

“The Devil’s Whore” And No More?

Even after leaving the monastery, however, Luther still struggled. He was still tempted to desire a righteousness he could see and feel, examine and admire, as his own private possession. He still wanted to be righteous in himself, not by faith, but sensibly. Thus, at times he portrays reason as a mistress or seductress, who tempts Christians to look for a “home-made righteousness” within rather than to an “alien righteousness” which we have only outside ourselves (extra nos) in Christ. At one point, he exclaims: “Reason is the devil’s whore and can do nothing but blaspheme and defile everything God speaks and does” (Luther’s Works 40: 175).

Luther was often brilliantly one-sided. This was his genius. Unfortunately, however, such statements have led some to conclude that he did not value reason or, worse, that he prized irrationality. This is false. A more positive statement on the place of reason comes from a sermon he preached in 1531, the humor of which would not have been lost on his Wittenberg congregation:

“In external and worldly matters let reason be the judge. For there you can calculate and figure out that a cow is bigger than a calf, that three ells are longer than one ell, that a gulden is worth more than a groschen, that a hundred guldens are more than ten guldens, and that it is better to place a roof over the house than under it. Stay with that. You can easily figure out how to bridle horses, for reason teaches you that. Prove yourself a master in that field. God has endowed you with reason to show you how to milk a cow, to tame a horse, and to realize that a hundred guldens are more than ten guldens. There you should demonstrate your smartness; there be a master and an apt fellow, and utilize your skill. But in heavenly matters and in matters of faith, when a question of salvation is involved, bid reason observe silence and hold still. Do not apply the yardstick of reason, but give ear and say: Here I cannot do it; these matters do not agree with reason as do the things mentioned above. There you must hold your reason in check and say: I do not know; I will not try to figure it out or measure it with my understanding, but I will keep still and listen; for this is immeasurable and incomprehensible” (Luther’s Works 23:84).

Yet even this statement does not do justice to the role of reason put into service of faith or sanctified by grace. Still, Luther’s point was that as enormously helpful as it can be (and as much as it may rightly tell us about ourselves), reason alone cannot tell us who we truly are.

Our Problem Since the Garden

The desire to know ourselves from ourselves rather than from God has been our problem all along.In Creation and Fall, Bonhoeffer discusses the difference between eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, which the serpent connects “to the promise of being like God [sicut Deus],” and living obediently in the image of God. Bonhoeffer compares “God and imago dei man against God and sicut deus man” and says the latter lives from “out-of-himself, in his un-derived existence, in his loneliness” and “out of a division of good and evil,” whereas the former, “bound to the word of God of the creator and living from him,” lives “in the unity of obedience” and in proper knowledge of himself.[3]

Our efforts, in other words, “to explain ourselves by ourselves instead of by our concrete confrontation by God,” Barth says, is precisely our sin and “perhaps the fundamental mistake in all erroneous thinking of man about himself is that he tries to equate himself with God and therefore to proceed on the assumption that he can regard himself as the presupposition of his own being.”[4]

Calvin knew this, which is why he begins his Institutes: “Nearly all the wisdom we possess … consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves.” As he elaborates in detail, contrary to philosophers ever since Socrates who teach “Know thyself” above all things, we cannot know ourselves truly apart from knowing God. Nor, contrary to speculative philosophers and theologians, can we know God truly apart from knowing him as our Redeemer or “until Christ the Mediator comes forward to reconcile him to us” (1.2.1).

Right knowledge of God and of ourselves is a twofold knowledge, not two kinds of knowledge, but one with two interdependent parts. Indeed, one is not possible without the other and is so interconnected it is difficult to know, Calvin says, where one begins and the other ends. But this much is clear: so long as we look only at ourselves we will never understand ourselves truly. We can only understand ourselves truly by looking to God.

To Whom Are We To Look and Listen?

This is also why telling people, “Let your conscience be your guide,” may not always be a good idea. Barth says: “Conscience, in Latin as in Greek, clearly means: to know with.” The question is always: “With whom?” With ourselves? With our peers? With other authorities? What counts, ultimately, is knowing “With God.”[5] We can betray our conscience, but our conscience can also betray us, depending on how it is shaped. This is why, as John Thompson explains so well in the previous essay, we ought to seek “A Correctable Conscience.”

The Reformers, in fact, did not regard conscience as such, or knowledge of ourselves from ourselves, a reliable witness as far as sin and salvation are concerned. On the contrary, Luther said: “If it depended on us, sin would very likely remain dormant forever. But God is able to awaken it effectively through the Law.” “Let God be true and every man a liar” (Rom. 3:4) meant to Luther that the believer must, again and again, “cease to believe in himself and believe in God,” and acknowledge “God truthful and himself a liar. For he disbelieves his own mind as something false in order to believe the word of God as the truth, even though it goes against all he thinks in his own mind.”[6]

Likewise, Calvin states: “When the apostle teaches that we should ‘work out our own salvation in fear and trembling’ [Phil. 2:12], he demands only that we become accustomed to honor the Lord’s power, while greatly abasing ourselves. For nothing so moves us to repose our assurance and certainty of mind in the Lord as distrust of ourselves, and the anxiety occasioned by the awareness of our ruin.” Calvin adds such anxiety [timor filialis] “renders us more cautious—not the kind that afflicts us and causes us to fall [timor servilis]—while the mind confused in itself recovers itself in God, cast down in itself is raised up in him, despairing of itself is quickened anew through trust in him” (Institutes 3.2.23). Thus, “if you contemplate yourself” apart from Christ, Calvin says, “that is sure damnation” (3.2.24), but knowing ourselves in Christ is life and peace.

Luther preached: “‘This is a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptance, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners; of whom I am chief’ (I Tim. 1:15). Ponder on this text and diligently arm yourself so that you will be prudent at all times––not only if your conscience is clear (apart from the struggle with your conscience), but also and particularly, when you have to contend with death and you are confronted with the greatest perils and dangers. This is when your conscience will be reminding you of the sins you have committed and it will be in a state of horror. Satan will appear before you as a mighty power and his intention will be to overwhelm you with the great burden of your sins flooding into your mind like a huge deluge. Satan will try to scare you away from Christ and will also try to chase you away from Him so that you will end up in despair. I say: ‘Remember that Christ did not offer Himself up for invented or exaggerated sins but for real sins––not for small insignificant sins but for great and coarse sins, not for just a couple sins here and there, but for all the sins in the world, not for sins that have been overcome and eliminated, but for scarlet and powerful sins that have still not been dispensed with.’”[7]

Luther never forgot his torments of conscience or how they made him feel. “A Christian, however,” he said, “is not guided by what he sees or feels; he follows what he does not see or feel. He remains with the testimony of Christ; he listens to His words and follows Him into the darkness” (Luther’s Works 22:306). “For,” as Paul says, “we live by faith, not by sight” (2 Cor. 5:7).

Few have stated more clearly what it means to live as a sinner saved by grace than Bonhoeffer: “the Christian is the [one] who no longer seeks his salvation, his deliverance, his justification in himself, but in Jesus Christ. He knows that God’s Word in Jesus Christ pronounces him guilty, even when he does not feel his guilt, and God’s Word in Jesus Christ pronounces him not guilty and righteous, even when he does not feel that he is righteous at all. The Christian no longer lives of himself, by his own claims and his own justification, but by God’s claims and God’s justification. He lives wholly by God’s Word pronounced upon him, whether that Word declares him guilty or innocent.” “If somebody asks him, Where is your salvation, your righteousness? He can never point to himself. He points to the Word of God in Jesus Christ, which assures him salvation and righteousness.” Thus, “The death and the life of the Christian is not determined by his own resources; rather he finds both only in the Word that comes to him from the outside, in God’s Word to him. The Reformers expressed it this way: Our righteousness is an ‘alien righteousness,’ a righteousness that comes from outside of us (extra nos).”[8] Christian, where is your salvation? The Reformers remind us where, which gives us good reason to rejoice!

The Reverend Richard E. Burnett, Ph.D. is the Executive Director and Managing Editor of Theology Matters

[1] Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon, 1950), 34–51.

[2] Ibid, 65.

[3] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Creation And Fall: A Theological Inter-pretation of Genesis 1–3 (New York: Macmillan, 1959), 70–71.

[4] Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics III/2:151.

[5] Karl Barth, The Faith of the Church (New York: Meridian Books, 1958), 67.

[6] Luther’s Works 25: 284. See Randall Zachman, The Assurance of Faith: Conscience in the Theology of Martin Luther and John Calvin (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993), 60.

[7] Luther’s Breviary: A Meditation for Each Day of the Year, ed.Thomas Seidel(Wartburg: Wartburg Verlag, 2007), 86.

[8] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Life Together (New York: Harper & Row, 1954), 21–22.